The Paris Agreement: What you need to know

The Paris Agreement is the latest and most important agreement for coordinating international action on climate change. But how much do you really know about the Paris Agreement? What does it seek to achieve, and how? Here are the answers you needed to know, all ahead of COP26 in October (don't worry, we'll get into what that is, too).

What is the goal of the Paris Agreement?

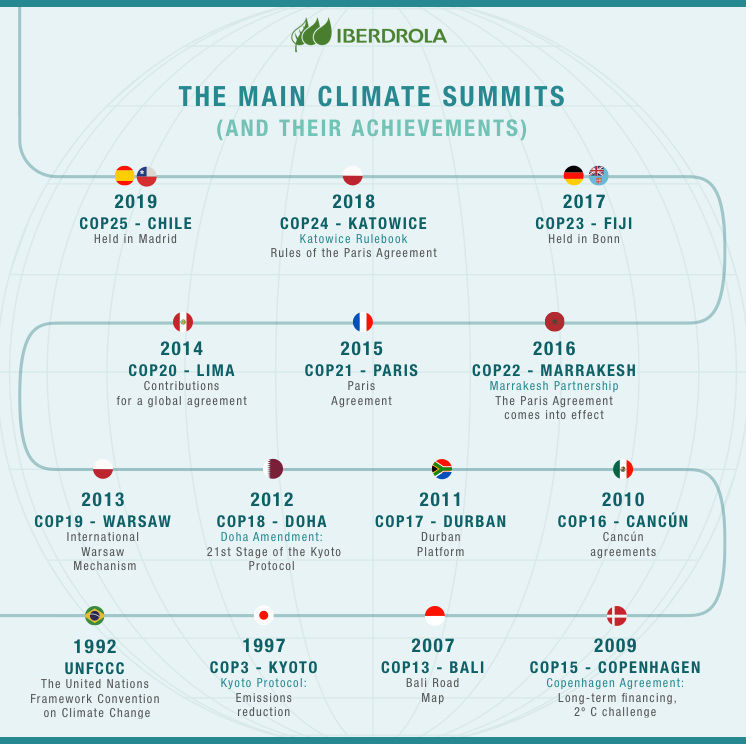

The Paris Agreement is the latest in a series of international agreements seeking to align global governments on a path toward meaningful climate action. It materialized, after much negotiation, out of the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) convened by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) in Paris, in December 2015.

The goal of the Paris Agreement is to provide a framework of cooperation through which member states seek to limit the rise in the planet’s average air temperature to no more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels. After objection from Pacific Island nations (who will be among the first to experience adverse effects of climate change), a clause was added that incorporated an aspirational target of no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

The Paris Agreement also outlines the timeline for a “net-zero” future for its members. In Article 4(1), it states that "Parties aim to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible" and will seek "balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century". By committing to this agreement, member states committed to a net-zero transition sometime between 2050-2100 and are signaling to markets and global industry that they need to plan accordingly.

There have been other climate agreements in the past. How is this one different?

As you can imagine, the process of aligning a large group of global stakeholders on climate action is not an easy task. Some wealthy countries (like the U.S.) don’t want to finance the lion’s share of climate adaptation efforts, while some less-wealthy countries argue that they shouldn’t be responsible for “cleaning up” the emissions generated by heavy emitters like China and the U.S.

Past international climate agreements faced challenges when trying to encompass these myriad interests. The Kyoto Protocol, a predecessor to the Paris Agreement, failed in part because it mandated emissions reductions targets, and charged most of the costs for achieving those targets to industrialized nations like the U.S. (we of course took offense at this, and refused to implement the 1997 Protocol).

The Paris Agreement takes a different approach: rather than penalizing members for failing to meet targets, it allows countries to voluntarily set their own level of ambition for climate change mitigation and incorporates accountability via regular review in an international forum. Negotiation continues on smaller pieces of the Agreement, such as joint financing mechanisms and technology sharing, which were part of Trump's reasoning for withdrawing the U.S. from the Agreement in 2015 (Biden reversed that decision in January 2021).

How does the Agreement seek to achieve its goal of a 2°C pathway?

Via the Paris Agreement framework, every five years each member country makes voluntary pledges called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). These NDCs outline what that country is going to do within their jurisdiction to help limit warming – thus “contributing” to the global goal of the Agreement.

A country’s NDCs can be as ambitious or lackluster as they’d like – but the Paris Agreement contains an interesting mechanism for publicly shaming any underachievers. Each year, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) convenes its member states at a Conference of the Parties (COP). At COP, countries are expected to share their NDCs (if it’s time to report new targets) and report on progress made towards meeting them. If a country submits unambitious NDCs or falls short of achieving their NDCs, it will be reviewed, debated, and publicly shamed by its peers in COP and reported on in the international press. It is expected that by being held accountable for progress in this public forum, the countries will be guilted into performance – both by their own citizens and by their global peers.

After five years, member countries are expected to submit new NDCs that are progressively more ambitious than their previous set of goals. This so-called “ratcheting mechanism” is designed to drive countries towards achieving a 2°C climate pathway.

So...will this actually work?

The jury is still out, and the verdict is being hotly debated.

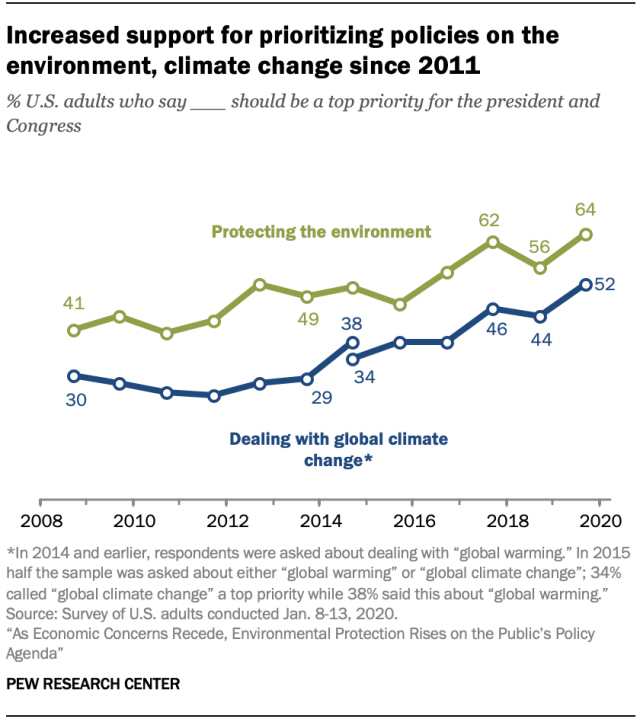

On the upside, the Paris Agreement side-steps many of the characteristics that scuppered its predecessors by using a flexible, self-determined framework for NDCs. It also relies on NGOs, local governments, and citizens to hold their leaders accountable to achieving NDCs – and with citizens demanding greater action on climate change in the face of dire scientific predictions, the heat is literally and figuratively on. Hopes are high that governments will read the writing on the wall and commit to bold action via the Agreement.

However, there are many who say the Paris Agreement doesn’t have what it takes to coordinate this massive and unprecedented transition. Critics specifically point out two important flaws in the Paris Agreement:

The first major issue is how to limit “free-riders”. While curtailing climate change is in the best interest of all countries around the world, there’s no mechanism to ensure that all countries contribute fairly to that reduction. This is known as the “free-rider problem”: because all countries benefit, regardless of their contribution, there is a strong temptation to simply coast off the reductions achieved by other countries. Climate researcher Robert Falkner explains: “One facet of the problem is that while climate change mitigation requires considerable investment in the short run, the benefits of stabilizing the global climate will materialize only in the medium to long run. This makes it difficult for governments to justify significant upfront expenditure, particularly given the brevity of electoral cycles…For many, then, the most rational line to take may seem the wait-and-see approach. And even if some emitters were to undertake major mitigation measures, they could not be certain that other emitters would reciprocate. Reducing national emissions amounts to the provision of a global ’public good’ from which all countries would benefit, with concomitant powerful free-riding incentives.” Of course, if everyone free-rides, then no one is reducing emissions – and no meaningful change is achieved.

The second challenge is that the Paris Agreement contains no penalties for underperformance. As mentioned above, it carefully sidesteps the binding international targets of its predecessors and instead relies on a process of voluntary, collective action as the main mechanism for achieving emissions reductions. But aside from public shaming, there is no penalty for failing to progress or act on NDCs. And with countries still struggling to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, leaders may be willing to take a hit on climate change in service of shorter-term priorities. Robert Falkner again: “In the case of climate change, as in other areas, the effectiveness of peer pressure will depend on two factors: first, the degree to which governments are sensitive to international opprobrium and reputational loss; and second, the number of countries that are non-compliant or fail to live up to international expectations. Unfortunately, the past record of international climate politics offers little comfort in this respect. Time and again, major emitters have shown themselves willing to accept a loss in international reputation when domestic economic priorities have been at stake.”

What should we expect at COP26?

In late October, COP26 will convene in Glasgow. With new warnings about approaching tipping points and growing demands for action, this COP is poised to be a watershed point in our global efforts to mitigate the worst effects of climate change.

At COP26, the represented countries will submit new NDCs which are to be achieved by 2030. They will also evaluate whether those NDCs are cumulatively sufficient to put us on a pathway to limiting global warming to 1.5-2°C above pre-industrial levels, as outlined by the Paris Agreement. NDC submissions at previous COP summits have fallen far short of this target, but this year feels different. “2021 is a crucial year in the fight against climate change,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres, “The world remains way off target in staying within the 1.5° limit of the Paris Agreement. This is why we need more ambition, more ambition on mitigation, ambition on adaptation and ambition on finance.”

Countries have been busily working on submitting the NDCs they plan to achieve by 2030, and per the ‘ratcheting’ mechanism of the Paris Agreement, these are meant to be more ambitious than NDCs they had planned to achieve by 2025 (you can read the U.S.’ previous NDCs here). An early snapshot of in-process NDCs in February revealed that mush greater ambition is needed.

International attention will be trained on Glasgow this October as COP26 convenes. In this do-or-die decade, everyone will be waiting to see if the Paris Agreement can indeed deliver on its promises and effectively shepherd the global community towards impactful climate action.

Cover image, credit: Paul Jordan Anderson, Doublehorn Photography.

Comments