Environmental Racism and Environmental Justice: A Place to Start

Today, we’re talking about the intersection of racism and the environment.

This is a post that has been in my Drafts folder, in one form or another, for at least a year. I’ve long wanted to say something about the white-ness of the environmental movement; about who has the luxury of creating environmental hazards and who has to live with the consequences of them. I really wanted to put in the research and do justice to the incredible complexity of this issue. But the longer I wrote, the more I felt like my “research” was really a white person’s attempt to find a guilt-absolving loophole.

I’ve been part of racism and injustice conversations long enough to observe that there is a horizon of diminishing returns to the facts: At some point, excessive research and fact-parsing analyses graduate from ‘germane background information’, to an escape tactic that absolves us of taking responsibility for changing our thoughts and behaviors. While I believe that we should be aware of the nuance of these issues, I don’t want the flood of data to distract you from taking meaningful action. So in that mind, and in keeping with the “beginner” spirit of this blog, I’ve made an effort to distill environmental racism and justice down to the most basic introductory points.

In approaching this topic, I do want to make clear one broad and important Fact: that environmental injustice is just one manifestation of the larger issue of racism. Racism is deeply woven into our American lives; the legacy of American slavery is one of egregious and still-unresolved oppression that has shaped the evolution of our modern nation in all its politics, policies, and psychology. This is a bitter pill for most white Americans to reckon with, and for many of us, it sadly may be a new one.

In looking at the last 50 years, many white Americans might have mistakenly concluded that racism, specifically toward Black people, is a thing of the past. But this is merely the proof of the old adage,"ignorance is bliss"; the recent deaths of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks, and many more have starkly corrected this notion, providing high-profile (but tragically, not uncharacteristic) reminders that racism is still very much at work in our society. As Dr. Nathalie Edmond told my yoga trainee class: this is not merely a case of a “few bad apples”, but a case of the entire orchard being grown in poisoned soil and forming twisted, diseased trees. The individual apples may not bear poison themselves, but they are nonetheless shaped by their environment. Knowingly or unknowingly, we are all shaped by the poison of racism. And if we care at all about the ideal of a free and equal society, it is incumbent upon us to see it, address it, and correct it.

With that said, we move on to this primer and an opening disclaimer. There are a lot of opinions circulating about the underlying components of racism and related terminology, which deserve more detail and examination than I am able to give in this limited space (for example, for the sake of economy, I have used the term ‘BIPOC’ or ‘communities of color’ throughout the following article, which I realize some may take offense at or find unspecific). This article is presented in effort, however imperfectly, to illuminate a facet of the broader issue, and to engage with the topic of racism rather than ignore. I am happy to receive your comments and feedback (see ‘Contact’ link at top), and I encourage you to use this as a starting point. Continue your own journey of growth and learning with extreme humility, patience, and empathy.

Environmental racism? Environmental justice? Definitions, please.

Let’s start off with a few basic definitions, shall we? If you Google these terms, you'll find several shades of the same basic idea, which can be distilled down to the following:

Environmental Justice: Broadly, environmental justice can be defined as the equal distribution of the by-products (waste) of an affluent society among all of its members.

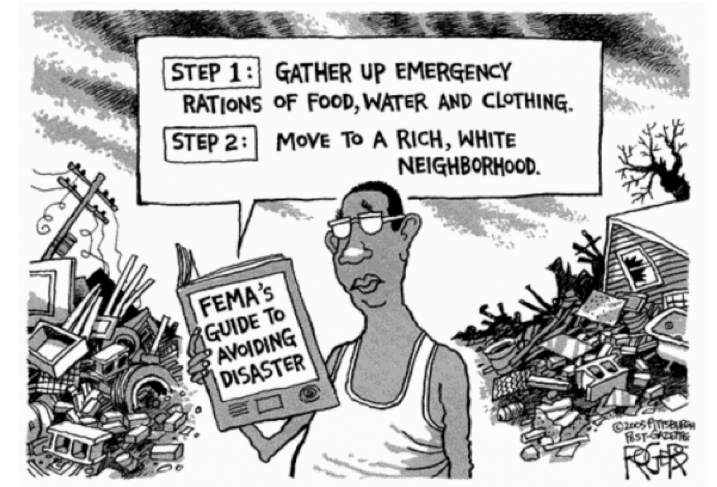

Environmental Racism: Again, the broad definition here: environmental racism is the unequal distribution of the by-products (waste) of an affluent society, with higher amounts of waste and toxic materials concentrated specifically in communities of color.

Here's what these definitions mean, in reality: In a perfectly equal society, we would all equally share the “bad” effects that come as by-products of our high quality of life:

If we want coal-powered electricity, we should all have to inhale some coal dust.

If we want cheap gas, we should all be ok with toxic waste in our water sources.

If we want cheap electronics, we should all have heaps of plastic eternally decaying in our backyards.

But reality is rarely so perfect - and as a society, we have tacitly agreed to the policy of relocating these undesirable after-effects to BIPOC communities.

How does environmental racism manifest? How does it affect BIPOC communities?

The manifestations of environmental racism are well-documented and can take many forms. Some examples include:

The legacy of redlining. Formerly redlined neighborhoods perpetuate a legacy of unequal treatment, this time in the guise of environmental hazard. The results of a recent study on redlining and climate found that “94% of studied areas display consistent city-scale patterns of elevated land surface temperatures in formerly redlined areas relative to their non-redlined neighbors by as much as 7 °C (45° F)”. Aside from just being uncomfortable, NPR notes that these higher temps can have dangerous effects: “Extreme heat kills more Americans every year than any other weather-related disaster, and heat waves are growing in intensity and frequency as climate change progresses.”

The location of industrial processing facilities in communities of color

The disposal of toxic waste in communities of color

Resistance to providing and maintaining safe, up-to-date infrastructure and sanitary services (hello Flint, Michigan)

Commandeering neighborhoods, community facilities, tribal lands and sacred cultural sites for government or private use

These actions affect communities of color in a variety of (often lethal) ways. Dr. Beverly Wright, a sociologist and CEO of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice (DSCEJ) at Dillard University, has compiled a disturbing list of the physical effects of environmental racism (full article here):

Polluted air: Communities of color are exposed to 40 percent more polluted air than White communities across the US, according to the NAACP’s 2012 “Coal-Blooded” study.

Are more likely to have polluting industries located in their communities: Though African-Americans make up 13 percent of the US population, a startling 68 percent live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant, compared to 56 percent of Whites, says the NAACP.

Are more likely to have toxic waste dumped in their communities, as was the case with the BP oil spill or the Tennessee Valley Authority.

These are just a handful of effects. Other effects include food apartheid and limited access to green space. Just last month, after conducting a study of 32 million pregnancies, a report concluded that the effects of climate change (increased temperatures, poorer air quality) lead to birth complications and death. These complications disproportionately affect Black women, and are "likely the result of several systemic problems", such as proximity of polluting industries and waste, unequal access to healthcare, and access to disposable income.

"The conclusions from scientists at the National Center for Environmental Assessment ... find that black people are exposed to about 1.5 times more particulate matter than white people, and that Hispanics had about 1.2 times the exposure of non-Hispanic whites ... Interestingly, it also finds that for black people, the proportion of exposure is only partly explained by the disproportionate geographic burden of polluting facilities, meaning the magnitude of emissions from individual factories appears to be higher in minority neighborhoods." - The Atlantic, Feb. 28, 2018

Why are communities of color targeted?

You may roll their eyes at this (“hello, racism”), but the question should be asked. More specifically, we might ask “are these communities targeted specifically because of race? Or are there other factors at play?” As a growing body of research shows, the “other factors” that are frequently referred to as "the real issue" are not supportable by research.

Poverty

The most frequent excuse one hears is poverty, and many have assumed that poverty is the more likely root of environmental inequity. Communities with higher rates of poverty generally have less organization and less political voice, and are less likely to organize into an empowered, strong resistance. Because of this, they have been historically and intentionally targeted as sites of industrial pollution. Communities of color (for systemic reasons elsewhere in our government and policies) often intersect with poverty, and so it might be concluded that race is a coincident, but not causal, determinant in environmental inequity. As a result, poverty has sometimes replaced racism as the root of environmental inequality.

But while scholarly research on environmental racism has been historically sparse, it is becoming clear on one fact: that race is distinct from poverty as a determinant of whether you live in a healthy or a polluted environment:

“A central question in the debate over the causes of environmental inequality is whether the differential levels of environmental quality are the result of class factors or racial dynamics - whether the bias of distribution of environmental hazards is a function of poverty rather than race. Are not minorities disproportionately targeted and impacted because they are disproportionately poor?...A growing number of studies on the distribution of specific environmental hazards and environmental quality by race and income show that race is an independent factor, not reducible to class, in predicting the distribution of environmental hazards...Recent, pioneering studies provide compelling evidence that environmental quality is mediated by race and socioeconomic status, directly linked to dynamics of discrimination and racial inequality in America, and cannot be separated from issues of equity.” - Raquel Pinderhughes, 'The Impact of Race on Environmental Quality'

This is not to say that poor communities are not also targets of environmental injustice - they are. But it is important to realize that race and income are two separate determinants of the environmental quality of a neighborhood.

A Question of ‘Care’

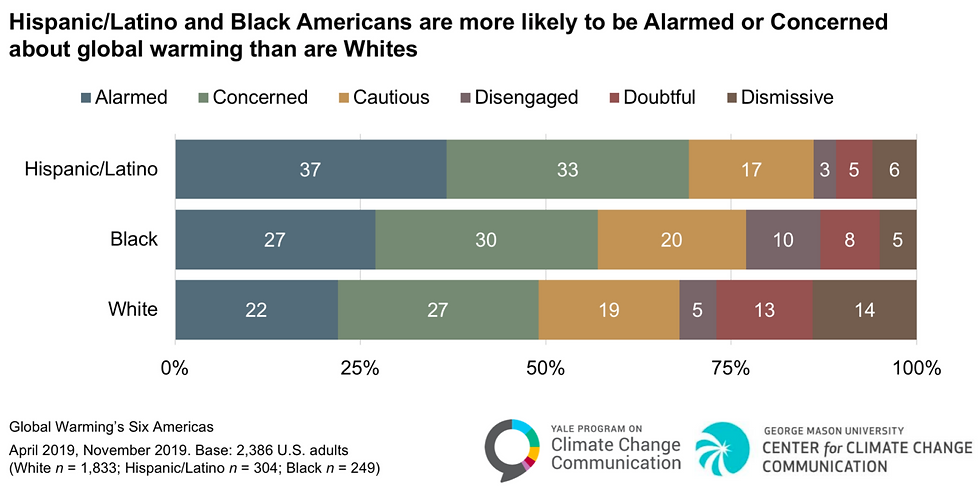

Another factor that is sometimes raised is the question of care: it is sometimes assumed that environmentalism is a “white people” issue, and that people of color are uninterested in issues of environmental health and sustainability. But this assumption has been disproved by several studies in recent years. In fact, according to a recent study from Yale, Americans of color are both more concerned about environmental issues and more likely to take action on those concerns than white Americans.

“Research suggests that people of color may be more concerned than Whites about climate change because they are often more exposed and vulnerable to environmental hazards and extreme weather events. One particularly important example is that people of color are more likely than Whites to be exposed to air pollution.” - Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, April 16, 2020

With these clarifications in place, we are left with the harder and more accurate truth: that environmental inequality is a result of racism and racial bias.

Ok. So then environmental justice means...what? How can I help, as just one person?

In contrast to environmental racism, environmental justice means redistributing the waste of our affluent society among everyone who enjoys and benefits from that society. This takes two obvious forms:

Remediating existing forms of environmental racism. This includes cleaning up industry, redistributing environmental burdens, and reversing policies and practices that perpetuate environmental racism.

Advocating for just solutions in the future. In addition to addressing past instances and practices of environmental racism, it is imperative that we remain alert to future instances, that we support efforts and take actions to resist environmental racism, and that we uplift the voices of those being targeted by these practices.

This second point surfaces a huge issue: the omission of voices of color from the environmental movement itself. Despite the fact that communities of color are disproportionately affected by the harshest realities of climate change and environmental degradation; despite the fact that people of color demonstrate a strong interest in environmental issues, there has been a dearth of diverse voices in the conversation - and in many cases, a deliberate suppression of those voices. Following the pattern set in other areas of American life, the loudest voices in the environmental movement are often still white.

It also presents a first step in personal action. This omission creates an imperative for white environmentalists (like you!) to advocate for and seek out diversity; to speak less so that others can speak more; to act as allies and followers rather than as leaders. It requires that we all become more educated: not just on issues of sustainability and the environment, but on how these issues intersect with other structures that house racial bias. It demands that we engage with the conversation, readily admitting our own failures and generous with our forgiveness of others’ failures while still driving towards change.

It also requires that we do things. Specifically, that we develop encyclopedic knowledge of our local and state issues, that we vote and volunteer in support of environmental justice and equality, and that we change our purchasing habits to support those businesses that are actively seeking an equal world.

Six Ways to Get Started:

Seek diversity in your feed: follow Jhanneu, Leah, Dominique, Cindy, Aja, Cristina, Alex, Corina, Katie.

Connect with the work happening at Intersectional Environmentalist.

Read through the New York Times' list of resources on environmental racism, and Dr. Robert Bullard's list of links.

Get involved in local advocacy efforts to protect public lands and influence diversity in the outdoors.

Consider where you spend your money; think deeply about who is oppressed and who is uplifted by the purchases and investments you make.

VOTE (but educate yourself first).

Yorumlar